the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Feasibility of irrigation monitoring with cosmic-ray neutron sensors

Heye Reemt Bogena

Markus Köhli

Johan Alexander Huisman

Harrie-Jan Hendricks Franssen

Olga Dombrowski

Accurate soil moisture (SM) monitoring is key in irrigation as it can greatly improve water use efficiency. Recently, cosmic-ray neutron sensors (CRNSs) have been recognized as a promising tool in SM monitoring due to their large footprint of several hectares. CRNSs also have great potential for irrigation applications, but few studies have investigated whether irrigation monitoring with CRNSs is feasible, especially for irrigated fields with a size smaller than the CRNS footprint. Therefore, the aim of this study is to use Monte Carlo simulations to investigate the feasibility of monitoring irrigation with CRNSs. This was achieved by simulating irrigation scenarios with different field dimensions (from 0.5 to 8 ha) and SM variations between 0.05 and 0.50 cm3 cm−3. Moreover, the energy-dependent response functions of eight moderators with different high-density polyethylene (HDPE) thickness or additional gadolinium thermal shielding were investigated. It was found that a considerable part of the neutrons that contribute to the CRNS footprint can originate outside an irrigated field, which is a challenge for irrigation monitoring with CRNSs. The use of thin HDPE moderators (e.g. 5 mm) generally resulted in a smaller footprint and thus stronger contributions from the irrigated area. However, a thicker 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding improved SM monitoring in irrigated fields due to a higher sensitivity of neutron counts with changing SM. This moderator and shielding set-up provided the highest chance of detecting irrigation events, especially when the initial SM was relatively low. However, variations in SM outside a 0.5 or 1 ha irrigated field (e.g. due to irrigation of neighbouring fields) can affect the count rate more than SM variations due to irrigation. This suggests the importance of retrieving SM data from the surrounding of a target field to obtain more meaningful information for supporting irrigation management, especially for small irrigated fields.

- Article

(3691 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

A reduction in soil moisture (SM) availability can negatively affect crop health, which is why irrigation is often employed to prevent yield reduction and crop failure connected to droughts and heat waves (Kukal and Irmak, 2019; Siebert et al., 2017; Tack et al., 2017; Webber et al., 2016; Zaveri and Lobell, 2019). Worldwide, ∼ 25 % of the cropped land is irrigated (Rost et al., 2008) to increase food production and stabilize yields, especially in arid and semiarid regions (Kamali et al., 2022; Troy et al., 2015). It is predicted that water scarcity will be a key challenge in ensuring food security in light of expected climate change (Elliott et al., 2014; Molden, 2013; Pisinaras et al., 2021). To meet this challenge, improvement of water use efficiency in irrigation is crucial (Abioye et al., 2020; Adeyemi et al., 2017). This can be achieved, for example, through an accurate monitoring of SM in space and time (Vereecken et al., 2008). Sensors that monitor SM variations are generally either large-scale remote sensing techniques that only sense shallow soil depths and are strongly influenced by vegetation and surface roughness (Bogena et al., 2010; Wagner et al., 2007; Walker et al., 2004) or point-scale instruments that only offer local information (Mohanty et al., 2017). Recently, cosmic-ray neutron sensors (CRNSs) have been identified as a promising method to close the gap between point- and large-scale measurements of SM due to their large footprint of tens of hectares (Bogena et al., 2015; Heistermann et al., 2021).

CRNSs detect neutrons that are produced by natural cosmic radiation. The number of epithermal neutrons is known to be negatively correlated with the abundance of hydrogen atoms near the soil surface, and thus with the SM near the CRNS (Desilets et al., 2010; Köhli et al., 2021; Zreda et al., 2008, 2012). CRNSs are not only sensitive to SM but also to snow cover (Bogena et al., 2020; Schattan et al., 2017) and, to a generally lesser degree, vegetation (Baatz et al., 2015), atmospheric water vapour (Rosolem et al., 2013), and intercepted water in the canopy and lattice water (Bogena et al., 2013). The accuracy of CRNS-based SM estimates is thus affected by environmental conditions. For example, the environmental neutron density and thus the count rate are higher for dry soils, which results in more accurate measurements compared to wet soils (Bogena et al., 2013; Desilets et al., 2010). Instrument design and set-up can also affect the accuracy of CRNS measurements of SM. Recent sensor developments have focused, for example, on enhancing neutron count rates to obtain a higher temporal resolution for SM estimation. This can be achieved with larger sensors or by using multiple counter tubes (Chrisman and Zreda, 2013; Schrön et al., 2018b). Additionally, neutrons detected by CRNSs are generally in the thermal (below 0.5 eV) or epithermal (0.5 eV to 0.5 MeV) energy regime (Weimar et al., 2020), with the former having smaller footprint and penetration depth as well as different sensitivity to SM and biomass (Jakobi et al., 2021, 2022). To enhance the detection of epithermal neutrons, the energy sensitivity (i.e. energy-dependent response function) of a CRNS (Köhli et al., 2021) can be shifted towards the epithermal energy range by using a high-density polyethylene (HDPE) moderator (Desilets et al., 2010; Weimar et al., 2020). In addition, a gadolinium-based (Ney et al., 2021) or cadmium-based (Andreasen et al., 2016) shielding can be used to prevent the detection of thermal neutrons (Desilets et al., 2010).

A CRNS provides SM information for an area of several tens of hectares and tens of centimetres deep into the soil (Köhli et al., 2015). Compared to point-scale SM monitoring sensors, a CRNS is non-invasive, offers passive and continuous measurements with relatively high temporal resolution, requires low maintenance (Schrön et al., 2018b), and is invariant to certain environmental variables such as soil temperature (Finkenbiner et al., 2019). In the context of agricultural applications, a CRNS can be placed in between or out of the way of routine production practices. It consequently does not present the logistic challenges associated with networks of directly inserted sensors, which need to be removed and reinstalled during harvest, planting, and other management actions (Franz et al., 2016). CRNS applications have increased rapidly in recent years, including validation of satellite-based remote sensing products (Montzka et al., 2017) and improvement of hydrological and land-surface model predictions (Baatz et al., 2017; Shuttleworth et al., 2013) among many other applications. In the upcoming years, additional coverage, real-time data availability, and rover-based measurements are expected to further increase the use of CRNSs (Dong et al., 2014; Jakobi et al., 2020), for example to study prolonged droughts or flood events (Bogena et al., 2022).

Cosmic-ray neutron sensing has shown potential for monitoring and informing irrigation (Franz et al., 2020). However, the most accurate results are obtained in environments where SM within the footprint is rather homogeneous (Schrön et al., 2017). Although Franz et al. (2013) indicated a rather small effect of horizontal SM heterogeneity on CRNS measurements under natural conditions, individual areas with contrasting SM can be wrongly represented by a single CRNS (Badiee et al., 2021; Schattan et al., 2019; Schrön et al., 2018a). Sub-footprint heterogeneity can be reconstructed using multiple instruments, but this comes with increased costs and necessitates further assumptions regarding spatial continuity (Heistermann et al., 2021). As a result, it can be difficult to distinguish local SM variations (Francke et al., 2022), such as the difference between the SM in a small irrigated field and its surroundings. Despite such limitations, Ragab et al. (2017) reported that CRNS measurements were useful for monitoring soil moisture deficit in the root zone, and Finkenbiner et al. (2019) found that information obtained from combined CRNS measurements and electrical conductivity surveys could improve water use efficiency in a field irrigated with a centre pivot system in Nebraska (USA). In addition, Baroni et al. (2018) reported a clear response of CRNSs to irrigation, although quantification of single irrigation events was not possible due to effects of precipitation and irrigation of nearby fields. In the case of drip irrigation, where the irrigated area is only a small portion of the volume sensed by the CRNS, the detection of irrigation-related SM variations can be more challenging. Li et al. (2019) were not able to accurately monitor drip irrigation with a standard CRNS in a citrus orchard in Spain. This was a consequence of the relatively small area wetted by drip irrigation, which resulted in a small mean SM change in the instrument footprint. However, better results could be achieved in irrigated fields with a larger wetted area, in drier regions, and for longer and more intense irrigation periods as well as by using instruments with higher count rates. These previous studies highlight that it is currently not clear if CRNSs can be used as an accurate stand-alone tool in irrigation management. In particular, the effects of the dimension of the irrigated area, SM variation due to irrigation, and the design of the sensor are largely unaddressed.

Within this context, the aim of this study is to analyse the feasibility of CRNS-based SM monitoring in irrigated environments. To achieve this, neutron transport and detection in irrigated environments was investigated with physics-based Monte Carlo simulations. These are widely used in CRNS studies (Andreasen et al., 2016) that are focused on, for example, the description of the footprint characteristics (Zreda et al., 2008) and the local site arrangement and instrument calibration strategies (Desilets and Zreda, 2013; Schrön et al., 2017). In this study, the Ultra Rapid Adaptable Neutron-Only Simulation (URANOS) model developed by Köhli et al. (2015) was used. Simulations were performed for five different dimensions of irrigated areas (i.e. 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 ha) and SM variations between 0.05 and 0.50 cm3 cm−3 both within and outside the irrigated area. To evaluate how detector design can help to improve irrigation monitoring, the energy-dependent response functions of eight different moderators were also considered. The analysis of this set of Monte Carlo simulations allowed us to investigate the effect of different moderators, dimensions of the irrigated area, and SM variations inside and outside the irrigated area on CRNS-based irrigation monitoring.

2.1 Soil moisture monitoring with CRNSs

CRNSs measure SM by detecting the environmental neutron density produced by cosmic radiation, which is inversely related to below- and aboveground hydrogen pools that surround the sensor. These environmental neutrons have different energies depending on the number and type of interactions that have occurred. Primary cosmic rays with energies around 1 GeV generate high-energy (larger than 20 MeV) neutrons in the atmosphere. By interacting with heavy atoms, these neutrons lose energy and become fast neutrons (0.5 to 20 MeV). The energy of these fast neutrons is further reduced by elastic collisions with lighter atoms (generally hydrogen), first to the epithermal regime (0.5 eV to 0.5 MeV) and finally to a thermal equilibrium (below 0.5 eV). CRNSs typically measure neutrons in the thermal to fast energy regimes (Köhli et al., 2021; Weimar et al., 2020). The measured neutron flux is affected by multiple hydrogen pools, such as soil water, water bodies, lattice water, and biomass. Typically, the CRNS signal is mainly controlled by SM variations, but the additional hydrogen pools can strongly influence the accuracy of the SM estimates (Baatz et al., 2015; Baroni et al., 2018; Iwema et al., 2021; Jakobi et al., 2020; Zreda et al., 2012). Generally, a CRNS is composed of one or more neutron detectors that can be bare (thermal–epithermal neutron detection) or moderated with HDPE (epithermal to fast neutron detection). More detailed information on the main detector components and physics can be found in Zreda et al. (2012), Schrön et al. (2018b), and Weimar et al. (2020).

2.2 CRNS footprint and penetration depth

The quantitative description of the horizontal area over which a CRNS measures is named “footprint”. Detected neutrons that had no contact with the ground (non-albedo neutrons) are, by definition, excluded from the footprint calculation. Thus, the footprint only depends on detected neutrons that had contact with the ground (albedo neutrons). Since CRNSs cannot detect the origin of a neutron and whether it had contact with soil nuclei, the footprint is generally obtained via neutron transport simulations. Although some studies suggested an asymmetric or “amoeba-like” footprint (Schattan et al., 2019; Schrön et al., 2022), most studies assume a simplified circular footprint that depends on the Euclidean distance between the points where neutrons had first contact with the ground and the point of detection. A quantile definition is widely used to define a distance within which most detected neutrons originate (Desilets and Zreda, 2013; Zreda et al., 2008). Commonly used radii are the one e-folding length (∼ 63 % of neutrons) and the two e-folding lengths (∼ 86 % of neutrons). The footprint varies depending on environmental conditions and instrument characteristics (Schrön et al., 2017). Monte Carlo simulations showed that the two e-folding lengths (R86) are ∼ 240 m in fully dry conditions and are reduced by up to 40 % with increasing SM and, to a lesser degree, with variations in humidity, vegetation, and other environmental variables (Köhli et al., 2015). The penetration depth of a CRNS also depends on SM and is higher below the instrument, where it ranges between 83 and ∼ 15 cm (Köhli et al., 2015) depending on SM. The characterization of the CRNS support volume in terms of footprint and measurement depth is a complex and ongoing research subject (Schrön et al., 2022), as shown by a range of recent simulation and field studies that further investigated the spatial sensitivity of SM determined with CRNSs (Badiee et al., 2021; Francke et al., 2022; Schrön et al., 2017) as well as the footprint of thermal neutrons (Jakobi et al., 2021).

2.3 Neutron transport modelling with URANOS

The URANOS model, which is freely available online (http://www.ufz.de/uranos, last access: 10 November 2022), was used in this study. This model was first developed to address neutron-only interactions and was later adapted to the cosmic-ray neutron problem (Köhli et al., 2015). URANOS is based on a Monte Carlo approach for the simulation of neutron transport and interactions with matter (Köhli et al., 2018). It is tailored to the study of neutron transport in environmental science, and thus certain processes such as gamma cascades or fission are neglected or represented by effective models. This reduces the computational effort and generally allows the simulation of a larger number of neutrons, which results in more accurate simulations (Köhli et al., 2015). In URANOS, neutrons are emitted from point sources that are randomly distributed within a user-defined source layer with energies sampled from a realistic spectrum matching that of the Earth's atmosphere (Sato, 2015). Then, URANOS uses a standard calculation routine that features a ray-casting algorithm for single neutron propagation and tracks the relevant physical interactions for millions of neutrons (e.g. elastic collisions, inelastic collisions, absorption, and emission processes such as evaporation). URANOS follows the ENDF (Evaluated Nuclear Data File) database standard implementations from Romano and Forget (2013) with cross-sections, energy distributions, and angular distributions obtained from the datasets of Chadwick et al. (2011) and Shibata et al. (2011).

2.4 Simulation set-up

The model domain in URANOS was composed of six (or seven) layers: one (or two) soil and five atmospheric layers. The soil layer extended to 1.6 m depth. The atmospheric layers extended from the soil surface to 1000 m height. The thickness of the five layers was 2, 0.5, 47.5, 30, and 920 m from the bottom to the top layer. The fourth layer was the source layer (from 50 to 80 m above the soil surface, respectively). The pressure of the atmosphere and of the air in the porous media was set to 1020 hPa. A humidity of 3 g cm−3 and a composition of 78 % nitrogen, 21 % oxygen, and 1 % argon were assumed. The soil bulk density was set to 1.43 g cm−3, and the porosity was set to 50 %.

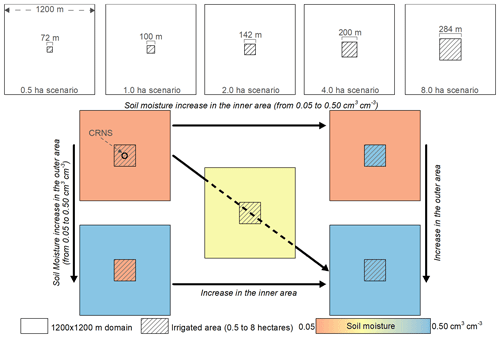

The simulation domain was 1200×1200 m (144 ha) with a resolution of 1 m. It was divided into two areas: (a) a square area at the centre of the domain with five different dimensions (i.e. 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 ha) and (b) the surrounding area. The SM in the inner and in the outer areas was modified independently with increments of 0.05 cm3 cm−3. Additionally, a 1 ha circular area and a 1 ha rectangular area (142×70 m) were simulated with SM variations in the inner area from 0.05 to 0.35 cm3 cm−3. These SM variations were applied homogeneously (both vertically and horizontally) within each area. Finally, for a 1 ha square inner area, simulations with two soil layers were produced, where the SM variation was applied only in the top 10 cm or 30 cm of soil. As in the previous circular and rectangular area scenarios, SM in the inner area varied from 0.05 to 0.35 cm3 cm−3. Figure 1 conceptually describes the simulation strategy taking the 8 ha scenario as an example. A first simulation is performed with a uniform SM of 0.05 cm3 cm−3 in both inner and outer areas. Then, the SM is varied either in the inner area, the outer area, or both areas. This results in 100 simulations with different SM combinations for each scenario and a total of 500 simulations. For each simulation, 108 neutrons were used as this provided sufficient precision and a reasonable computation time (Köhli et al., 2015).

Figure 1Examples of the dimensions of the inner area relative to the simulation domain and schematization of the simulation design and set-up with an example for the 8 ha scenario. A 1200×1200 m domain is used with an inner area of 8 ha and a CRNS placed at its centre. The SM is then systematically varied in the inner and outer area with increments of 0.05 cm3 cm−3 for a total of 100 simulations.

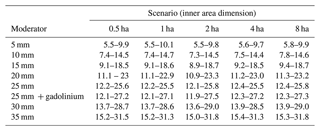

2.5 Investigated moderators and their energy-dependent response functions

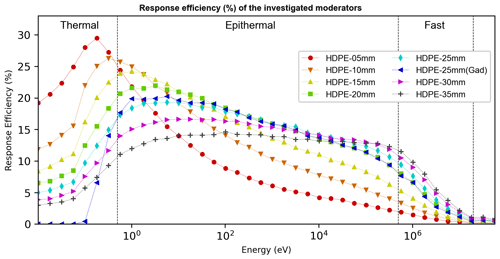

Each simulation provided information on the simulated neutrons that crossed the detector at the centre of the domain (e.g. energy at detection, coordinates of first soil contact). The detector was a vertical cylinder of 9 m radius positioned in the second atmospheric layer (2 to 2.5 m aboveground) and at the centre of the simulation domain. However, not all neutrons that pass through the detector tube are detected, whereby the probability of detection depends on neutron energy and direction, as well as on sensor characteristics such as the used conversion gas, geometrical configuration, and moderator type (Köhli et al., 2018). Different moderators are commercially available and are typically made of HDPE of various thicknesses. In this study, we investigated the use of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35 mm HDPE moderators. Furthermore, an additional gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3) shield was investigated for a moderator composed of 25 mm HDPE. As was proposed by Desilets et al. (2010), a 25 mm HDPE moderator thickness was selected for the detector shielded with gadolinium. This is supported by Weimar et al. (2020), who found only small differences in response for moderator thicknesses of 20 to 27.5 mm HDPE with gadolinium shielding. Thus, the combination of gadolinium shielding with other moderator thicknesses was not considered. The energy-dependent response functions of the investigated moderators as reported by Köhli et al. (2018) are shown in Fig. 2. Detectors with thin HDPE moderators (e.g. 5 mm HDPE) are highly sensitive to thermal neutrons, while detectors with thicker moderators have a higher sensitivity to epithermal neutrons. The 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding has similar sensitivity to epithermal neutrons as the non-shielded variant but shows less sensitivity to thermal neutrons (Köhli et al., 2018; Weimar et al., 2020). In fact, such shielding can absorb and thus prevent the detection of more than 90 % of the incoming thermal neutrons (Ney et al., 2021), which have a smaller footprint and different sensitivity to SM than epithermal neutrons (Jakobi et al., 2021; Jakobi et al., 2022; Rasche et al., 2021). A cubic spline of each response function was applied to the output of each simulation, and a weight was assigned to each neutron depending on its energy at detection. Then, these weights were summed to obtain the number of detected neutrons and subsequently used in a weighted calculation of the R86. The effect of the angular distribution of the neutrons was not considered here as it was assumed to be negligible, which is reasonable given the absence of changes (e.g. vegetation, atmospheric pressure, humidity) in the vicinity of the detector.

Figure 2Energy-dependent response functions of different moderators made of 5 to 35 mm thick high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and, in the case of 25 mm HDPE, an additional gadolinium-based thermal shielding.

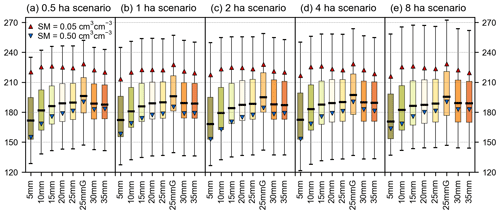

Figure 3Boxplots of R86 in metres for different moderator types and size of the inner area, i.e. (a) 0.5, (b) 1, (c) 2, (d) 4, and (e) 8 ha. Each boxplot refers to one moderator type (100 combinations of SM) and shows the minimum and maximum values with whisker caps, the interquartile range with bars, and the median with a black line. Blue and red triangles show R86 values for homogeneous SM of 0.05 and 0.50 cm3 cm−3, respectively.

2.6 Investigation of the feasibility of irrigation monitoring with CRNSs

The changes in R86 due to SM variations in the inner and outer areas as well as the use of different moderators were analysed. Although a footprint description that relies on a single value can be misleading (Badiee et al., 2021; Schrön et al., 2022), the R86 represents a standard in CRNS applications and was thus selected to investigate the simulations of this study. Here, the initial hypothesis is that a relatively small R86 is beneficial when monitoring irrigation in small fields as a lower contribution from the surrounding area could be expected. To analyse the Monte Carlo simulation runs, the detected neutrons in each simulation were divided into two types: albedo and non-albedo neutrons. Albedo neutrons carry environmental SM information and were further divided into neutrons that originated within the inner area and neutrons that originated in the outer area. Here, it was assumed that the neutrons that originate within the inner irrigated field carry the bulk of the information of interest. Although neutrons that originate outside the irrigated field can have occasional within-field interactions before reaching the CRNS (Köhli et al., 2015), these were considered of secondary importance for the scope of this study. In a following step, the relative changes in detected neutrons with SM variations were investigated. For a given dimension of the inner area, moderator type, and SM of the outer area (10 simulations), the highest simulated neutron count was set to 100 %. Then, the results of the other nine simulations were scaled to that count rate. The influence of the moderator type, the dimension of the irrigated area, and the SM in the outer area were then compared. Here, larger changes in detected neutrons were considered beneficial as this leads to higher accuracy of the SM estimates.

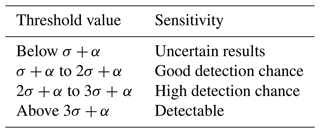

Next, the sensitivity to irrigation events was assessed in more detail for the moderator type that provided the largest relative changes in detected neutrons. Starting from homogeneous SM conditions in the simulated domain, an irrigation event was assumed to increase the SM in the irrigated area by either 0.05 or 0.10 cm3 cm−3. Such SM variation was applied to the entire soil profile. For the 1 ha square area, the SM variation was separately applied to the top 10 and 30 cm and to the entire soil profile. The initial homogeneous SM conditions were between 0.05 and 0.25 cm3 cm−3 as this is the relevant range for irrigation applications. The selected detection thresholds, shown in Table 1, were based on the relative error in the simulations:

where N1 and N2 are the neutron counts obtained with the initial and final SM conditions, respectively. In addition to σ, a value of α=1 % was included in each threshold to represent a generic detection uncertainty limit for a detector that can achieve ∼ 1000 counts per hour and aggregation times of <12 h that are relevant in SM monitoring (Schrön et al., 2022).

Table 1Detection thresholds that were adopted to investigate the CRNS sensitivity to irrigation events

Lastly, relative changes in detected neutrons due to homogeneous SM variations within the simulation domain were compared with those due to SM variations that occur in the inner or in the outer areas only. Again, the moderator type that had provided the largest relative changes in detected neutrons was selected. For each dimension of the irrigated area (100 simulations), the highest simulated neutron count was set to 100 %. The reduced sensitivity of the detection–SM relationship in the case of SM variations that occur only in the inner area was assessed. Here, a lower reduction in sensitivity was considered beneficial for irrigation monitoring. Also, the influence of the SM in the outer area on the count rate was compared to that of SM variations in the inner area. A strong influence of the SM in the outer area was considered disadvantageous for irrigation monitoring.

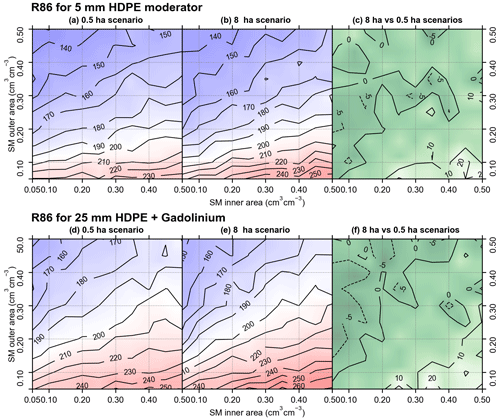

Figure 4Variation in R86 with SM using a 5 mm HDPE moderator for the (a) 0.5 ha and (b) 8 ha scenario and using a 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding for the (d) 0.5 ha and (e) 8 ha scenario. The differences between the 8 ha and 0.5 ha scenarios are shown in (c) for the 5 mm HDPE moderator and in (f) for the 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding. Here, negative values indicate that the footprint of the 8 ha scenario is smaller than that of the 0.5 ha scenario and vice versa.

3.1 CRNS footprint variations with SM heterogeneity and moderator type

The analysis of the CRNS footprint can be useful to understand the general distance from which the measured neutrons originate. The boxplots of R86 for all moderators and for different dimensions of the irrigated field are shown in Fig. 3. In general, the footprint increases when a thicker HDPE moderator is used and increases further when gadolinium shielding is added. Additionally, there is a trend towards a larger variability in the footprint size with SM variations when larger irrigated areas are considered. Generally, the largest R86 values are obtained using a 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding (e.g. min = 147, med = 196, and max = 273 m in the 8 ha scenario), whereas the lowest values are obtained with a 5 mm HDPE moderator (e.g. min = 127, med = 162, and max = 238 m in the 0.5 ha scenario). Nonetheless, for each dimension of the irrigated area, the difference in R86 obtained with different moderators and shielding is rather small and on the order of 10 to 20 m only. Such differences in R86 may thus have limited influence on CRNS measurements of small, irrigated fields.

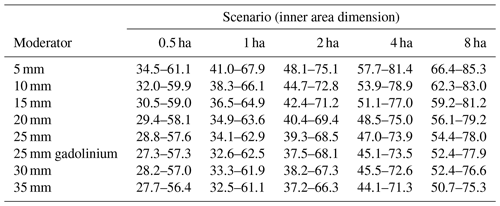

Table 2Minimum and maximum percentage of detected (albedo plus non-albedo) neutrons originating within the inner area depending on SM conditions with different moderators and different scenarios.

A more in-depth analysis of how R86 changes with SM variation is shown in Fig. 4 for a 5 mm HDPE moderator and for a 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding. The value of R86 depends on the SM of both the inner and outer area. Similar patterns in R86 variation with SM are found when other moderators are used (not shown). For example, for a 5 mm HDPE moderator, the highest R86 value in the 0.5 ha scenario is ∼ 234 m for high SM in the inner and low SM in the outer area (bottom right in Fig. 4a). The R86 decreases to ∼ 220 m when the SM in the inner area is reduced to 0.05 cm3 cm−3. A more pronounced decrease in R86 to ∼ 132 m occurs when the SM in the outer area is increased up to 0.50 cm3 cm−3. When the size of the inner area increases (Fig. 4b), the general trends in R86 with SM remain rather constant except for simulations where SM is high in the inner area and low in the outer area (bottom right corners). For these conditions, R86 tends to increase with increasing size of the inner area. For example, R86 is ∼ 258 m in the 8 ha scenario (Fig. 4b), which is almost 15 m larger than the R86 in the 0.5 ha scenario (∼ 234 m) for a SM of 0.50 cm3 cm−3 in the inner area and 0.05 cm3 cm−3 in the outer area. Similar considerations can be drawn for a 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding (Fig. 4d–f).

In previous studies, the smallest R86 was often assumed to occur for the highest SM in the CRNS surroundings. This is true for homogeneous SM conditions but may be different for heterogeneous SM distributions (Schrön et al., 2022). When the SM of the inner area is low and that of the outer area is high, the outer area becomes a less important source of neutrons, and thus the footprint is reduced. An opposite effect occurs when the inner SM is high and the outer SM is low. In this case, the inner area is a smaller source, and the neutrons from the outer area become more important, resulting in a larger footprint. For example, with a 5 mm HDPE moderator (Fig. 4a) the R86 of a 0.5 ha field reduces by 39.9 % when SM increases from 0.05 to 0.50 cm3 cm−3 in the outer area, whereas the same SM increase in the inner area enlarges R86 by 6.4 %. For a 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding, these percentages are 37.2 % and 9.9 %, respectively.

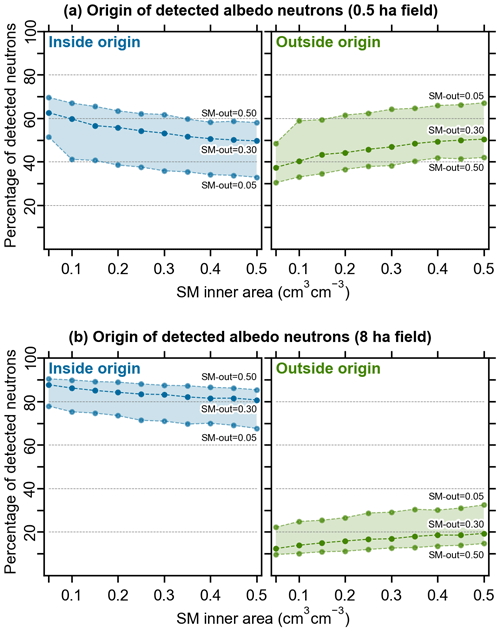

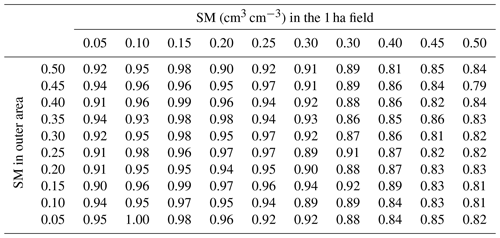

3.2 Detected albedo neutrons and their origin

For each dimension of the simulated inner area and for each moderator type, Table 2 shows the minimum and maximum percentages of detected (albedo plus non-albedo) neutrons that originate in the inner area depending on SM conditions. This percentage represents the detected neutrons that originate within an irrigated field and thus carry the bulk of the information of interest in case of irrigation applications. Considerable differences are found between simulations depending on the SM in the inner and outer area. The dimension of the irrigated area also influences the results. In particular, 27.7 % to 61.1 % of the detected neutrons originate from within a 0.5 ha irrigated field, whereas larger fields show higher percentages (e.g. 50.7 % to 85.3 % from within an 8 ha field). In addition, thinner moderators generally show a higher percentage of detected neutrons from the inner area.

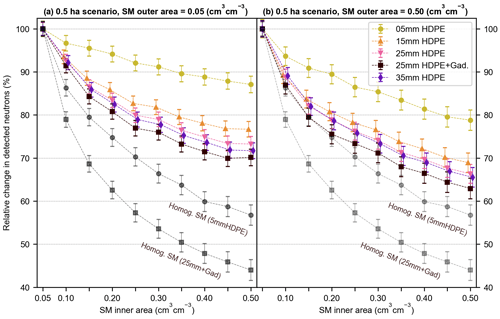

Figure 6Relative change in number of detected neutrons due to SM variations obtained using different moderators (i.e. 5, 15, 25, and 35 mm HDPE and 25 mm HDPE with gadolinium shielding) for (a) 0.05 and (b) 0.50 cm3 cm−3 SM in the outer area of a 0.5 ha field. The error bars indicate the relative error in the simulations. Grey circles and squares indicate the relative change for two selected moderators when the SM changes from 0.05 to 0.50 cm3 cm−3 are applied to the entire simulation domain.

Figure 5 shows the variation in the percentage of detected albedo neutrons that originate in the inner or in the outer area for the 0.5 ha scenario as a function of the SM of both areas for a detector with 25 mm HDPE moderator and gadolinium shielding, which shows the lowest percentages in Table 2. Non-albedo neutrons are not considered in Fig. 5, and the reader is referred to Appendix A for a more detailed description of such detected non-albedo neutrons. Clearly, the fraction of neutrons originating in the inner and outer area strongly depends on SM. The percentage of neutrons originating in the inner area is smallest when the inner area is wet and the outer area is dry (31.4 %). This percentage increases up to 58.0 % if the SM in the inner area is reduced to 0.05 cm3 cm−3 and then to 69.6 % when the SM of the outer area increases to 0.50 cm3 cm−3. The percentage of neutrons originating in the outer area shows the opposite trend. From these results, it is clear why CRNS applications focused on irrigation of small fields can face considerable challenges. Especially in small irrigated fields, the number of detected neutrons that originate outside the irrigated area can be higher than the number of neutrons that originate inside of the irrigated area. This is especially true when the SM outside the irrigated area is relatively low, which is often the case when the inner area is irrigated. Figure 5b presents the same analysis for an 8 ha field. Here, the percentage of neutrons from the inner area is higher than in the 0.5 ha scenario and shows a lower overall variation. Again, the lowest percentage of detected neutrons originating from the inner area (67.6 %) is found when the inner area is wet and the outer area is dry, whereas the highest value (90.4 %) is found with reversed SM conditions.

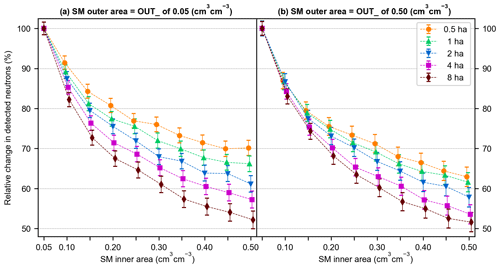

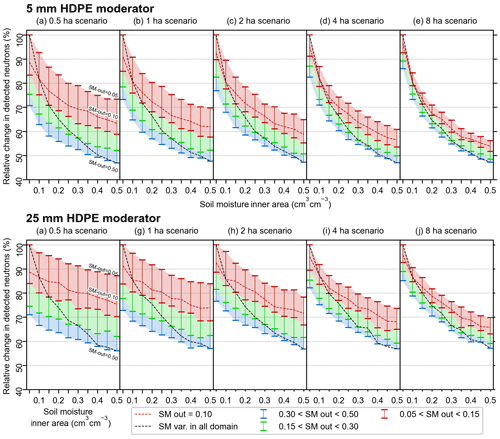

3.3 Effect of spatial heterogeneity on the relationship between neutron counts and SM

The relationship between neutron count rate and SM has been mostly investigated for homogeneous SM conditions. Here, we also explore the effect of SM variations that occur only within an inner area that surrounds the instrument (e.g. through irrigation). We considered sizes of the inner irrigated area from 0.5 to 8 ha and two opposite wetness situations for the outer area (i.e. SM of 0.05 and 0.50 cm3 cm−3). In addition, we considered the effect of the thickness of the moderator and additional shielding on the number of detected neutrons. In Fig. 6 and in Fig. 7, the neutron counts of the different simulations are scaled to the case with the highest count rates (SM of 0.05 cm3 cm−3 everywhere in the simulated domain). Generally, neutron count rates show a non-linear negative relationship with increasing SM in the irrigated area. The detector with a 5 mm HDPE moderator shows the smallest relative changes in neutron counts (Fig. 6). Thicker HDPE moderators (i.e. 15, 25, and 35 mm) result in larger relative changes. The largest difference in relative changes is observed between a 5 and a 15 mm HDPE moderator, whereas the differences between a 25 and a 35 mm HDPE moderator are rather small. The highest relative change in number of detected neutrons occurs for a 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding. Nonetheless, the described sensitivities are lower than with a homogeneous SM change in the entire domain (grey circles and squares in Fig. 6). The relatively high sensitivity of the 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding seems to contradict the relatively large R86 values as well as the relatively low percentage of detected neutrons that originate within the irrigated area for such a moderator. This is attributed to small relative variations in the R86 between different moderators and to the low number of detected thermal neutrons (< 5 %), which only contain limited SM information (see Appendix B). The SM in the outer area also has an influence on the results, although to a lesser degree. For example, a SM of 0.50 cm3 cm−3 in the outer area (Fig. 6b) leads to greater variations in detected neutrons than a SM of 0.05 cm3 cm−3 in the outer area (Fig. 6a).

The neutron count rates obtained with a 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding for irrigated areas ranging from 0.5 to 8 ha are shown in Fig. 7. An increased size of the irrigated area results in larger relative changes in the number of detected neutrons with SM variations, especially when the outer area is dry (Fig. 7a). Higher SM of 0.50 cm3 cm−3 in the outer area (Fig. 7b) results in larger relative changes in the number of detected neutrons, although this is mostly the case for relatively small dimensions of the irrigated area. For the 8 ha scenario, the impact of the SM in the outer area is very limited.

Generally, larger relative changes in detected neutrons with SM variations lead to an improved performance of a given CRNS in a certain environment. Thus, our analysis shows that the CRNS performance in an irrigated environment depends on both the moderator type and the SM outside of the irrigated area. However, the effect of different moderator types on the performance is stronger. A relatively thin HDPE moderator will generally result in low changes in the neutron count rate with SM variations, independent from the dimension of the irrigated field. A thicker HDPE moderator will provide higher neutron count changes and thus better sensitivity to SM changes in the inner area. Overall, a 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium thermal shielding achieves the best results.

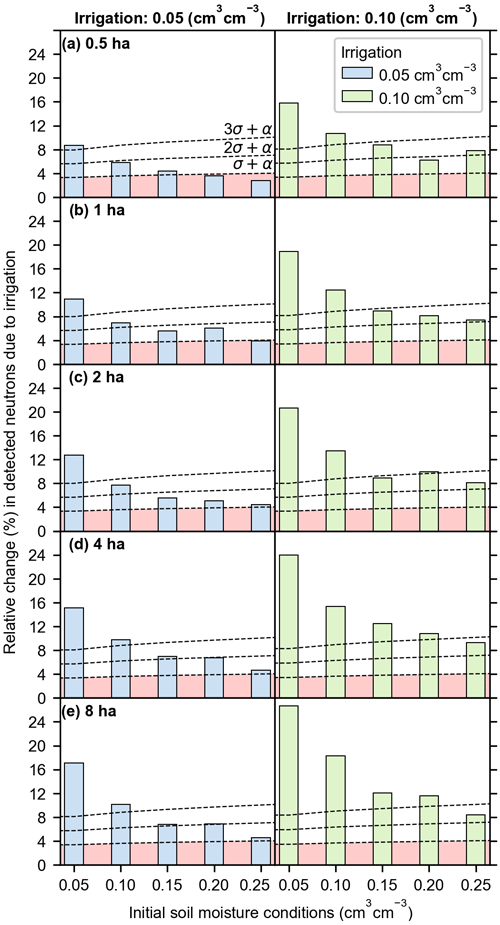

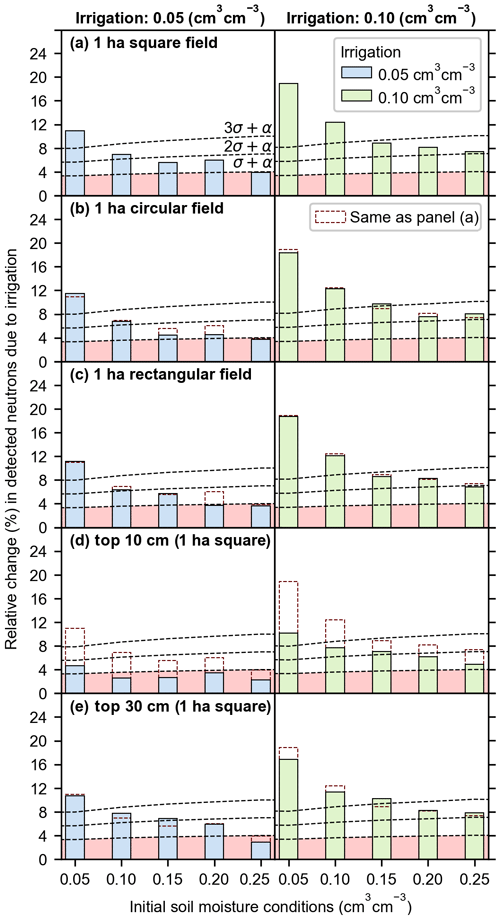

3.4 CRNS sensitivity to irrigation events

The sensitivity of a CRNS is further analysed to assess if it is possible to detect irrigation events in fields between 0.5 and 8 ha in size (Fig. 8). A 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding is used as it provides larger relative changes in the neutron count rate compared to the other investigated moderators. An irrigation event is assumed to increase the SM of the irrigated area by 0.05 or by 0.10 cm3 cm−3 starting from a homogeneous SM condition within the domain. The detection thresholds (see Fig. 8) are based on the relative error (σ) of the simulations (Eq. 1), which varied between 2.3 % and 3.4 % depending on the number of detected neutrons.

Figure 8CRNSs' chance of detecting irrigation events of 0.05 and 0.10 cm3 cm−3 (blue and green bars, respectively) in (a) 0.5, (b) 1, (c) 2, (d) 4, and (e) 8 ha irrigated fields. The bars show the relative change in detected neutrons induced by the irrigation event, while the dashed black lines show the prescribed detection certainty thresholds. The red area below the σ+α threshold indicates uncertain detection.

As shown in Fig. 8, an irrigation event that leads to a 0.05 cm3 cm−3 increase in SM can be detected with CRNSs (relative change in detected neutrons higher than 3σ+α) when the initial SM of the simulation domain is 0.05 cm3 cm−3. This is the case for all five investigated dimensions of the irrigated area. In the case of 4 and 8 ha fields, detection of this type of irrigation event is also achieved with an initial SM of 0.10 cm3 cm−3. For initial SM larger than 0.05 cm3 cm−3, the chance of detecting irrigation events depends on the dimension of the irrigated area, with larger irrigated fields yielding higher detection chances. Overall, the detection of a 0.05 cm3 cm−3 irrigation event is uncertain (relative change in detected neutrons lower than σ+α) when the initial SM is 0.20 cm3 cm−3 or higher in a 0.5 ha field (Fig. 8a) or 0.25 cm3 cm−3 in 1 ha field (Fig. 8b). Irrigation events that induce larger SM variations of 0.10 cm3 cm−3 result in larger relative changes in detected neutrons and thus have a higher chance of detection. Here, the CRNS detects irrigation events with initial SM up to 0.10 cm3 cm−3 in 0.5, 1, and 2 ha fields and with initial SM up to 0.20 cm3 cm−3 in 4 and 8 ha fields. If the investigation of a 0.10 cm3 cm−3 irrigation event is extended to higher initial SM (i.e. 0.30 to 0.40 cm3 cm−3), the only uncertain detection (lower than σ+α) is that of an initial SM of 0.40 cm3 cm−3 in a 0.5 ha field (not shown).

3.5 Influence of SM in the outer area

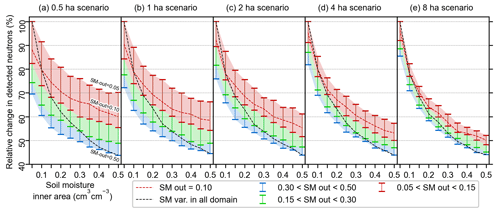

In fields between 0.5 and 8 ha, a CRNS is not only sensitive to the irrigation of the target field but also to SM variations in the outer area (e.g. due to irrigation of neighbouring fields). It is thus important to assess the impact of SM variations that occur outside the field of interest. Figure 9 shows the relationships between SM variations that occur in the inner area, in the outer area, or in both areas as well as the resulting relative changes in detected neutrons for a 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding. SM variations that are limited to the irrigated field show a reduced sensitivity of the relative change in neutron count rate compared to the case where SM variations occur homogeneously in the entire domain, which is due to the influence of the SM in the outer area. The strongest reduction in the sensitivity of this relationship is found for the 0.5 ha field (Fig. 9a). The sensitivity increases with larger dimensions of the irrigated area, and the observed reduction is lowest in the case of the 8 ha field (Fig. 9e).

Figure 9Relative changes in detected neutrons due to SM variations in (a) 0.5, (b) 1, (c) 2, (d) 4, and (e) 8 ha irrigated areas. The dashed black line shows SM variations that are homogeneous within the simulated domain. The dashed red lines and the error bars indicate SM variations that occur only within the irrigated area for a different SM in the outer area.

In the case of a 0.5 ha irrigated field, SM variations in the outer area generally induce a higher relative change in detected neutrons compared to SM variations that occur within the irrigated area. For example, a SM variation from 0.05 to 0.10 cm3 cm−3 in the outer area (Fig. 9a) induces a larger relative change (−11.8 %) compared to the same SM variation in the inner area (−8.6 %). With larger irrigated areas, the influence of the outer area is reduced. In the 8 ha scenario, a SM variation from 0.05 to 0.10 cm3 cm−3 in the inner area induces a larger relative change in detected neutrons than that of a SM variation from 0.05 to 0.50 cm3 cm−3 in the outer area. These results suggest that it may be necessary to obtain SM information from the surroundings of a target field in real-world applications of CRNS-based irrigation monitoring.

It is also of interest to reduce this analysis to a smaller range of SM in the outer area (i.e. 0.05 to 0.15 cm3 cm−3) as this is generally the case in irrigated agricultural environments (shaded red area in Fig. 9). In the case of 0.5 and 1 ha fields, a SM variation of 0.10 cm3 cm−3 in the outer area (red error bars in Fig. 9a–b) produces a relative change in the neutron count rate that is higher than that of an irrigation event of 0.05 cm3 cm−3. This is not the case when the initial SM of the domain is 0.05 cm3 cm−3 in the 2 ha scenario (Fig. 9c), 0.05 to 0.15 cm3 cm−3 in the 4 ha scenario (Fig. 9d), and 0.05 to 0.20 cm3 cm−3 in the 8 ha scenario (Fig. 9e). Overall, even if the range of the SM in the outer area is reduced, it can still have a considerable impact on the CRNS. This again underlines the importance of obtaining information on the SM in the outer area, especially in the case of relatively small irrigated fields.

The results of this study suggest that irrigation monitoring with CRNSs is feasible for field dimensions and SM conditions that are relevant in irrigation applications. However, it is important to emphasize here that the presented results constitute a best-case scenario as it assumes a square shape of the irrigated area, homogeneous SM changes (both horizontally and vertically) in the inner irrigated area, and stable SM conditions in the surroundings. An additional complexity could be represented by the influence of vegetation or air humidity. For example, air humidity affects R86 (Köhli et al., 2015) and may thus modify the contribution to detected neutrons of the irrigated field. Moreover, heterogeneous vertical SM distributions or different dimensions of the irrigated field, such as irregular or elongated shapes, might be more challenging for irrigation monitoring with CRNSs. Figure 10 shows the sensitivity of a CRNS with a 25 mm HDPE moderator and gadolinium shielding to irrigation events that increase the SM of the irrigated area by 0.05 or by 0.10 cm3 cm−3 starting from a homogeneous SM condition for different shapes of the irrigated area. The comparison between a circular (56 m radius), rectangular (142×70 m), and a square field of 1 ha (Fig. 10a–c) shows that there is a small change in CRNS performance for given SM variations for different field geometries. However, the differences are small, and the overall feasibility of irrigation monitoring with CRNS is not affected. Figure 10 also shows the sensitivity to irrigation events when only the first 10 cm or 30 cm of soil is wetted in a 1 ha square field. When irrigation affects SM only in the first 10 cm of soil (Fig. 10d), the sensitivity of the CRNS is strongly reduced. This is especially the case for SM variations of 0.05 cm3 cm−3, where the CRNS is able to detect irrigation only when the initial SM is 0.05 cm3 cm−3. However, it should be noted that SM variations of 0.05 and 0.10 cm3 cm−3 correspond to irrigation events of 5 and 10 mm. This rather small irrigation amount might correspond to the initial SM variation during a larger irrigation event or to frequent events (e.g. daily irrigation). When irrigation affects SM in the first 30 cm of soil, the sensitivity of a CRNS is comparable to that of a homogeneous vertical distribution of SM (Fig. 10a and e). The only differences are a drop from high to good detection chances for a 0.05 cm3 cm−3 SM variation and from certain to high detection chances for a 0.10 cm3 cm−3 SM variation when the initial SM is 0.15 cm3 cm−3. Overall, Fig. 10 suggests that a small change in the field shape and irrigation affecting just the top 30 cm of soil will only have a small influence on the feasibility of irrigation monitoring with CRNSs. However, it has to be noted that these results are based only on a limited number of simulations, and real-world studies should assess in more detail the influence of the shape of the irrigated field in addition to the impact of the within-field SM heterogeneity.

Figure 10CRNSs' chance of detecting irrigation events of 0.05 and 0.10 cm3 cm−3 (blue and green bars, respectively) in (a) a 1 ha squared field, (b) a 1 ha circular field, and (c) a 1 ha rectangular field and for SM variations that affect only the top (d) 10 and (e) 30 cm of soil for a 1 ha squared field. The bars show the relative change in detected neutrons induced by the irrigation event, while the dashed black lines show the prescribed detection certainty thresholds. In panels (b–e), the dashed red bars indicate the results of panel (a) (1 ha squared field). The red area below the σ+α threshold indicates uncertain detection.

Another aspect that needs further investigation is the role of SM variations in the surroundings of a target irrigated field. Information on such SM variations may be necessary to correct CRNS-based SM products in not only relatively small fields (up to 2 ha) but also larger ones. When a CRNS is installed in an irrigated field in place of a sensor network, the CRNS could be supported by a single and inexpensive point-scale SM monitoring instrument installed outside the target field. This would not substantially increase the installation and maintenance costs and would not interfere with agricultural management. Moreover, a single point-scale device could support multiple CRNSs in an agricultural area if irrigated fields are sufficiently distanced and if the SM in the unmanaged area is relatively homogeneous in space. However, in small fields (e.g. < 0.5 ha) that have relatively homogeneous SM, a small sensor network could be more effective than a CRNS. Within this context, Monte Carlo simulations of neutron transport represent an added value as they inform about the relative contribution from the surroundings of an irrigated field to the neutron count. Future research should investigate if generalized neutron transport simulations are sufficiently accurate or if simulations should be tailored to a target irrigated area. As a result, Monte Carlo simulation results could be employed before installation to provide farmers with an estimate of the costs and benefits of a CRNS-based irrigation monitoring system.

This study explores the feasibility of irrigation monitoring with CRNSs by using Monte Carlo neutron transport simulations. Specifically, it investigates the influence of the moderator type, the dimensions of the irrigated area, and SM variations within and outside the irrigated area. Results show that the CRNS footprint (R86) depends on both the SM in the irrigated area and its surroundings and, to a lesser degree, the moderator type and the dimension of the irrigated area. Generally, detectors with thinner HDPE moderators result in smaller footprints, although differences between the investigated moderators are relatively small. Regarding the origin of detected neutrons, a considerable fraction of the detected neutrons can originate from outside the irrigated region, which may represent a challenge in CRNS-based irrigation monitoring. This fraction varies considerably with the size of the irrigated area. Relatively higher contributions from the irrigated field are obtained for larger sizes of the irrigated area (e.g. 28 % to 61 % in 0.5 ha and 51 % to 85 % in 8 ha); higher SM outside the irrigated area; and, to a lesser degree, detectors with thin HDPE moderators. Despite a relatively larger R86 combined with lower contributions from the irrigated field, thicker HDPE moderators and the addition of a thermal shielding result in higher relative changes in detected neutrons with respect to SM variations. Thus, such moderator types are expected to bring improvements in CRNS-based irrigation monitoring.

A CRNS with a 25 mm HDPE moderator and gadolinium shielding can detect irrigation events that increase SM by 0.05 cm3 cm−3 even in fields as small as 0.5 ha when the SM in the entire simulated domain is 0.05 cm3 cm−3. Detection is uncertain in a 0.5 ha field when initial SM is 0.20 cm3 cm−3 or higher and again uncertain in a 1 ha field when initial SM is 0.25 cm3 cm−3 or above. Higher detection chances are found in the case of irrigation events that increased SM by 0.10 cm3 cm−3. For a 1 ha irrigated area, the use of a circular or rectangular shape instead of a square shape and SM increases in the first 30 cm of soil instead of the entire soil profile did not result in considerable changes in the CRNS sensitivity. In contrast, when SM was increased only in the first 10 cm of soil (e.g. small daily events or the initial stage of larger irrigation event), a considerable reduction in sensitivity was observed. Generally, larger irrigated fields, lower initial SM, and higher SM variations due to irrigation provide higher chances of detection. Using the same moderator, the relationship between relative changes in detected neutrons and SM variations for irrigated fields shows a reduced sensitivity compared to the case of homogeneous SM variations within the entire simulated domain. Such sensitivity reduction is due to the influence of SM from the outer area and is stronger in small irrigated fields compared to large ones. If SM in the outer area of 0.5 and 1 ha fields is between 0.05 and 0.15 cm3 cm−3, it is generally not possible to distinguish whether a relative change in detected neutrons is due to irrigation or to SM variations in the surroundings. In contrast, in an 8 ha field, irrigation-related SM variations of 0.05 cm3 cm−3 can be identified up to a maximum SM of 0.20 cm3 cm−3, independently from the SM of the surrounding area. The results suggest the importance of obtaining information on the SM of the outer area in real-world applications of CRNS-based irrigation monitoring.

Overall, this study shows that CRNSs can be successfully employed in irrigation monitoring for both field dimensions and SM conditions that are relevant in irrigation applications. Real-world conditions may nevertheless prove challenging due to the presence of additional factors and limitations that were not considered in this study. For example, vertical and horizontal heterogeneous SM variations within the irrigated field should be investigated in more detail in future studies as well as different shapes of the irrigated field. Moreover, the use of SM information from the surroundings of an actual irrigated field with limited size could be considered to correct CRNS-based irrigation products by combining actual measurements with Monte Carlo simulations. Prior to installation, Monte Carlo simulations could also be employed to assess the costs and benefits of a given detector in a specific irrigated environment. In the long term, the combination of simulations and real-world installations should be considered to establish CRNSs as a decision support system for irrigation management and thus provide an additional tool to improve water use efficiency in agriculture.

In all the 500 simulations, the percentage of detected non-albedo neutrons varied with SM variations and with the type of moderator (Table A1). Non-albedo neutrons represented a considerable percentage of the total detected neutrons. No meaningful variations were obtained with different dimensions of the irrigated area. Thick moderators resulted in higher percentages of detected non-albedo neutrons compared to thin moderators (e.g. 5.5 % to 9.9 % with a 5 mm HDPE moderator and 15.2 % to 31.8 % with a 35 mm HDPE moderator).

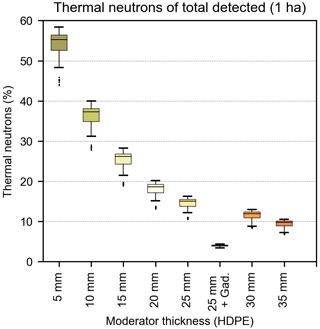

Thermal neutrons were found to have a smaller footprint compared to epithermal neutrons (Jakobi et al., 2021). The number of detected thermal neutrons and their percentage among all detected neutrons changes abruptly when different moderators are used (Fig. B1). A moderator of 5 mm HDPE results in thermal neutrons being above the 50 % level of detected neutrons. Such percentage can be reduced by increasing the thickness of the HDPE moderator and by adding a gadolinium shielding. Moderators that detect more thermal neutrons will result in a smaller footprint compared to other detectors (see Figs. 3 and 4) and, likely, in more detected neutrons originating within an irrigated field (see Table 2).

Table B1 shows that the variation in detected thermal neutrons that originate within a 1 ha irrigated field is rather small with a 5 mm HDPE moderator (although it should be noted that the relative errors are not negligible as detected thermal neutrons range between ∼ 700 and ∼ 800). Consequently, thermal neutrons can concentrate the instrument footprint over a small area (e.g. an irrigated field), but this might not be followed by an added value in the detection of SM changes within such an area.

Table B1Thermal neutrons detected with a 5 mm HDPE moderator that originate within a 1 ha field expressed as a fraction of the maximum value (i.e. 840 thermal neutrons detected with SM of 0.10 cm3 cm−3 in the inner area and 0.05 cm3 cm−3 in the outer area).

Figure C1 shows the relationship between SM variations (that occur in the inner area, in the outer area, or in both) and the consequent relative change in detected neutrons as well as the influence of the SM outside the irrigated field. This is shown for 5 mm HDPE (Fig. C1a–e) and 25 mm HDPE moderators (Fig. C1f–j). Compared to a 25 mm HDPE moderator with gadolinium shielding (Fig. 9), the 25 mm HDPE and 5 mm HDPE moderators show a generally lower sensitivity and higher influence of the SM outside the irrigated field, especially for the 5 mm HDPE moderator version.

Figure C1Relative changes in detected neutrons due to SM variations in (a) 0.5, (b) 1, (c) 2, (d) 4, and (e) 8 ha irrigated areas for a 5 mm HDPE moderator and in (f) 0.5, (g) 1, (h) 2, (i) 4, and (l) 8 ha for a 25 mm HDPE moderator. The dashed black line shows SM variations that are homogeneous within the simulated domain. The dashed red lines and the error bars indicate SM variations that occur only within the irrigated area for a different SM in the outer area.

Data are available upon contacting the authors. The URANOS model can be downloaded at the following address: http://www.ufz.de/uranos (last access: 29 June 2022).

The paper was conceptualised by CB, HRB and MK. Methods were developed by CB, HRB and MK. Investigation was performed by CB and MK. The methodology was finalised by CB, HRB, MK, JAH, HJHF and OD. The original manuscript draft was prepared by CB. The subsequent manuscript versions were written and edited by all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Markus Köhli holds a CEO position at StyX Neutronica GmbH.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This research received support from the ATLAS project funded through the EU's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 857125 and from the DFG 425 (German Research Foundation) via the project 357874777, research unit FOR 2694 Cosmic Sense.

This research has been supported by Horizon 2020 (ATLAS; grant no. 857125) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. 357874777).

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the Forschungszentrum Jülich.

This paper was edited by Mehrez Zribi and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abioye, E. A., Abidin, M. S. Z., Mahmud, M. S. A., Buyamin, S., Ishak, M. H. I., Abd Rahman, M. K. I., Otuoze, A. O., Onotu, P., and Ramli, M. S. A.: A review on monitoring and advanced control strategies for precision irrigation, Comput. Electron. Agr., 173, 105441, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105441, 2020.

Adeyemi, O., Grove, I., Peets, S., and Norton, T.: Advanced monitoring and management systems for improving sustainability in precision irrigation, Sustainability, 9, 353, https://doi.org/10.3390/su9030353, 2017.

Andreasen, M., Jensen, K. H., Zreda, M., Desilets, D., Bogena, H., and Looms, M. C.: Modeling cosmic ray neutron field measurements, Water Resour. Res., 52, 6451–6471, 2016.

Baatz, R., Bogena, H., Hendricks Franssen, H. J., Huisman, J., Montzka, C., and Vereecken, H.: An empirical vegetation correction for soil water content quantification using cosmic ray probes, Water Resour. Res., 51, 2030–2046, 2015.

Baatz, R., Hendricks Franssen, H.-J., Han, X., Hoar, T., Bogena, H. R., and Vereecken, H.: Evaluation of a cosmic-ray neutron sensor network for improved land surface model prediction, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 2509–2530, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-2509-2017, 2017.

Badiee, A., Wallbank, J. R., Fentanes, J. P., Trill, E., Scarlet, P., Zhu, Y., Cielniak, G., Cooper, H., Blake, J. R., and Evans, J. G.: Using additional moderator to control the footprint of a COSMOS Rover for soil moisture measurement, Water Resour. Res., 57, e2020WR028478, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR028478, 2021.

Baroni, G., Scheiffele, L., Schrön, M., Ingwersen, J., and Oswald, S.: Uncertainty, sensitivity and improvements in soil moisture estimation with cosmic-ray neutron sensing, J. Hydrol., 564, 873–887, 2018.

Bogena, H., Herbst, M., Huisman, J., Rosenbaum, U., Weuthen, A., and Vereecken, H.: Potential of wireless sensor networks for measuring soil water content variability, Vadose Zone J., 9, 1002–1013, 2010.

Bogena, H., Huisman, J., Baatz, R., Hendricks Franssen, H. J., and Vereecken, H.: Accuracy of the cosmic-ray soil water content probe in humid forest ecosystems: The worst case scenario, Water Resour. Res., 49, 5778–5791, 2013.

Bogena, H., Huisman, J., Güntner, A., Hübner, C., Kusche, J., Jonard, F., Vey, S., and Vereecken, H.: Emerging methods for noninvasive sensing of soil moisture dynamics from field to catchment scale: A review, WIRES Water, 2, 635–647, 2015.

Bogena, H., Herrmann, F., Jakobi, J., Brogi, C., Ilias, A., Huisman, J., Panagopoulos, A., and Pisinaras, V.: Monitoring of snowpack dynamics with cosmic-ray neutron probes: A comparison of four conversion methods, Front. Water, 2, 19, https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2020.00019, 2020.

Bogena, H. R., Schrön, M., Jakobi, J., Ney, P., Zacharias, S., Andreasen, M., Baatz, R., Boorman, D., Duygu, M. B., Eguibar-Galán, M. A., Fersch, B., Franke, T., Geris, J., González Sanchis, M., Kerr, Y., Korf, T., Mengistu, Z., Mialon, A., Nasta, P., Nitychoruk, J., Pisinaras, V., Rasche, D., Rosolem, R., Said, H., Schattan, P., Zreda, M., Achleitner, S., Albentosa-Hernández, E., Akyürek, Z., Blume, T., del Campo, A., Canone, D., Dimitrova-Petrova, K., Evans, J. G., Ferraris, S., Frances, F., Gisolo, D., Güntner, A., Herrmann, F., Iwema, J., Jensen, K. H., Kunstmann, H., Lidón, A., Looms, M. C., Oswald, S., Panagopoulos, A., Patil, A., Power, D., Rebmann, C., Romano, N., Scheiffele, L., Seneviratne, S., Weltin, G., and Vereecken, H.: COSMOS-Europe: a European network of cosmic-ray neutron soil moisture sensors, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 14, 1125–1151, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-1125-2022, 2022.

Chadwick, M. B., Herman, M., Obložinský, P., Dunn, M. E., Danon, Y., Kahler, A., Smith, D. L., Pritychenko, B., Arbanas, G., and Arcilla, R.: ENDF/B-VII. 1 nuclear data for science and technology: cross sections, covariances, fission product yields and decay data, Nucl. Data Sheets, 112, 2887–2996, 2011.

Chrisman, B. and Zreda, M.: Quantifying mesoscale soil moisture with the cosmic-ray rover, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 17, 5097–5108, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-5097-2013, 2013.

Desilets, D. and Zreda, M.: Footprint diameter for a cosmic-ray soil moisture probe: Theory and Monte Carlo simulations, Water Resour. Res., 49, 3566–3575, 2013.

Desilets, D., Zreda, M., and Ferré, T. P.: Nature's neutron probe: Land surface hydrology at an elusive scale with cosmic rays, Water Resour. Res., 46, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009WR008726, 2010.

Dong, J., Ochsner, T. E., Zreda, M., Cosh, M. H., and Zou, C. B.: Calibration and validation of the COSMOS rover for surface soil moisture measurement, Vadose Zone J., 13, https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2013.08.0148, 2014.

Elliott, J., Deryng, D., Müller, C., Frieler, K., Konzmann, M., Gerten, D., Glotter, M., Flörke, M., Wada, Y., Best, N., Eisner, S., Fekete, B. M., Folberth, C., Foster, I., Gosling, S. N., Haddeland, I., Khabarov, N., Ludwig, F., Masaki, Y., Olin, S., Rosenzweig, C., Ruane, A. C., Satoh, Y., Schmid, E., Stacke, T., Tang, Q., and Wisser, D.: Constraints and potentials of future irrigation water availability on agricultural production under climate change, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, 3239–3244, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222474110, 2014.

Finkenbiner, C. E., Franz, T. E., Gibson, J., Heeren, D. M., and Luck, J.: Integration of hydrogeophysical datasets and empirical orthogonal functions for improved irrigation water management, Precis. Agric., 20, 78–100, 2019.

Francke, T., Heistermann, M., Köhli, M., Budach, C., Schrön, M., and Oswald, S. E.: Assessing the feasibility of a directional cosmic-ray neutron sensing sensor for estimating soil moisture, Geosci. Instrum. Meth., 11, 75–92, 2022.

Franz, T. E., Zreda, M., Ferre, T., and Rosolem, R.: An assessment of the effect of horizontal soil moisture heterogeneity on the area-average measurement of cosmic-ray neutrons, Water Resour. Res., 49, 6450–6458, 2013.

Franz, T. E., Wahbi, A., Vreugdenhil, M., Weltin, G., Heng, L., Oismueller, M., Strauss, P., Dercon, G., and Desilets, D.: Using cosmic-ray neutron probes to monitor landscape scale soil water content in mixed land use agricultural systems, Appl. Environ. Soil Sci., 2016, 4323742, https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/4323742, 2016.

Franz, T. E., Wahbi, A., Zhang, J., Vreugdenhil, M., Heng, L., Dercon, G., Strauss, P., Brocca, L., and Wagner, W.: Practical data products from cosmic-ray neutron sensing for hydrological applications, Front. Water, 2, 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2020.00009, 2020.

Heistermann, M., Francke, T., Schrön, M., and Oswald, S. E.: Spatio-temporal soil moisture retrieval at the catchment scale using a dense network of cosmic-ray neutron sensors, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 25, 4807–4824, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-4807-2021, 2021.

Iwema, J., Schrön, M., Koltermann Da Silva, J., Schweiser De Paiva Lopes, R., and Rosolem, R.: Accuracy and precision of the cosmic-ray neutron sensor for soil moisture estimation at humid environments, Hydrol. Process., 35, e14419, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14419, 2021.

Jakobi, J., Huisman, J. H., Schrön, M., Fiedler, J., Brogi, C., Vereecken, H., and Bogena, H. R.: Error estimation for soil moisture measurements with cosmic-ray neutron sensing and implications for rover surveys, Front. Water, 2, 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2020.00010, 2020.

Jakobi, J., Huisman, J. A., Köhli, M., Rasche, D., Vereecken, H., and Bogena, H.: The footprint characteristics of cosmic ray thermal neutrons, Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2021GL094281, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL094281, 2021.

Jakobi, J. C., Huisman, J. A., Fuchs, H., Vereecken, H., and Bogena, H.: Potential of thermal neutrons to correct cosmic-ray neutron soil moisture content measurements for dynamic biomass effects, Water Resour. Res., 58, e2022WR031972, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022WR031972, 2022.

Kamali, B., Lorite, I. J., Webber, H. A., Rezaei, E. E., Gabaldon-Leal, C., Nendel, C., Siebert, S., Ramirez-Cuesta, J. M., Ewert, F., and Ojeda, J. J.: Uncertainty in climate change impact studies for irrigated maize cropping systems in southern Spain, Sci. Rep., 12, 1–13, 2022.

Köhli, M., Schrön, M., Zreda, M., Schmidt, U., Dietrich, P., and Zacharias, S.: Footprint characteristics revised for field-scale soil moisture monitoring with cosmic-ray neutrons, Water Resour. Res., 51, 5772–5790, 2015.

Köhli, M., Schrön, M., and Schmidt, U.: Response functions for detectors in cosmic ray neutron sensing, Nuclear instruments and methods in physics research section A: Accelerators, spectrometers, detectors and associated equipment, 902, 184–189, 2018.

Köhli, M., Weimar, J., Schrön, M., Baatz, R., and Schmidt, U.: Soil moisture and air humidity dependence of the above-ground cosmic-ray neutron intensity, Front. Water, 2, 66, https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2020.544847, 2021.

Kukal, M. S. and Irmak, S.: Irrigation-limited yield gaps: trends and variability in the United States post-1950, Environ. Res. Commun., 1, 061005, https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7620/ab2aee, 2019.

Li, D., Schrön, M., Kohli, M., Bogena, H., Weimar, J., Jiménez Bello, M. A., Han, X., Martínez-Gimeno, M. A., Zacharias, S., Vereecken, H., and Hendricks Franssen, H. J.: Can drip irrigation be scheduled with cosmic-ray neutron sensing?, Vadose Zone J., 18, 1–13, 2019.

Mohanty, B. P., Cosh, M. H., Lakshmi, V., and Montzka, C.: Soil moisture remote sensing: State-of-the-science, Vadose Zone J., 16, 1–9, 2017.

Molden, D.: Water for food water for life: A comprehensive assessment of water management in agriculture, Taylor & Francis Group, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849773799, 2013.

Montzka, C., Bogena, H. R., Zreda, M., Monerris, A., Morrison, R., Muddu, S., and Vereecken, H.: Validation of spaceborne and modelled surface soil moisture products with cosmic-ray neutron probes, Remote Sens., 9, 103, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9020103, 2017.

Ney, P., Köhli, M., Bogena, H., and Goergen, K.: CRNS-based monitoring technologies for a weather and climate-resilient agriculture: realization by the ADAPTER project, 2021 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry (MetroAgriFor), 3–5 November 2021, Trento-Bolzano, Italy, 203–208, https://doi.org/10.1109/MetroAgriFor52389.2021.9628766, 2021.

Pisinaras, V., Paraskevas, C., and Panagopoulos, A.: Investigating the Effects of Agricultural Water Management in a Mediterranean Coastal Aquifer under Current and Projected Climate Conditions, Water, 13, 108, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13010108, 2021.

Ragab, R., Evans, J., Battilani, A., and Solimando, D.: The cosmic-ray soil moisture observation system (Cosmos) for estimating the crop water requirement: new approach, Irrig. Drain., 66, 456–468, 2017.

Rasche, D., Köhli, M., Schrön, M., Blume, T., and Güntner, A.: Towards disentangling heterogeneous soil moisture patterns in cosmic-ray neutron sensor footprints, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 25, 6547–6566, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-6547-2021, 2021.

Romano, P. K. and Forget, B.: The OpenMC monte carlo particle transport code, Ann. Nucl. Energ., 51, 274–281, 2013.

Rosolem, R., Shuttleworth, W. J., Zreda, M., Franz, T. E., Zeng, X., and Kurc, S.: The effect of atmospheric water vapor on neutron count in the cosmic-ray soil moisture observing system, J. Hydrometeorol., 14, 1659–1671, 2013.

Rost, S., Gerten, D., Bondeau, A., Lucht, W., Rohwer, J., and Schaphoff, S.: Agricultural green and blue water consumption and its influence on the global water system, Water Resour. Res., 44, 9, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007WR006331, 2008.

Sato, T.: Analytical model for estimating terrestrial cosmic ray fluxes nearly anytime and anywhere in the world: Extension of PARMA/EXPACS, PloS one, 10, e0144679, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144679, 2015.

Schattan, P., Baroni, G., Oswald, S. E., Schöber, J., Fey, C., Kormann, C., Huttenlau, M., and Achleitner, S.: Continuous monitoring of snowpack dynamics in alpine terrain by aboveground neutron sensing, Water Resour. Res., 53, 3615–3634, 2017.

Schattan, P., Köhli, M., Schrön, M., Baroni, G., and Oswald, S. E.: Sensing area-average snow water equivalent with cosmic-ray neutrons: The influence of fractional snow cover, Water Resour. Res., 55, 10796–10812, 2019.

Schrön, M., Köhli, M., Scheiffele, L., Iwema, J., Bogena, H. R., Lv, L., Martini, E., Baroni, G., Rosolem, R., Weimar, J., Mai, J., Cuntz, M., Rebmann, C., Oswald, S. E., Dietrich, P., Schmidt, U., and Zacharias, S.: Improving calibration and validation of cosmic-ray neutron sensors in the light of spatial sensitivity, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 5009–5030, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-5009-2017, 2017.

Schrön, M., Rosolem, R., Köhli, M., Piussi, L., Schröter, I., Iwema, J., Kögler, S., Oswald, S., Wollschläger, U., and Samaniego, L.: Cosmic-ray neutron rover surveys of field soil moisture and the influence of roads, Water Resour. Res., 54, 6441–6459, 2018a.

Schrön, M., Zacharias, S., Womack, G., Köhli, M., Desilets, D., Oswald, S. E., Bumberger, J., Mollenhauer, H., Kögler, S., and Remmler, P.: Intercomparison of cosmic-ray neutron sensors and water balance monitoring in an urban environment, Geosci. Instrum. Meth., 7, 83–99, 2018b.

Schrön, M., Köhli, M., and Zacharias, S.: Signal contribution of distant areas to cosmic-ray neutron sensors – implications on footprint and sensitivity, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2022-219, 2022.

Shibata, K., Iwamoto, O., Nakagawa, T., Iwamoto, N., Ichihara, A., Kunieda, S., Chiba, S., Furutaka, K., Otuka, N., and Ohsawa, T.: JENDL-4.0: a new library for nuclear science and engineering, J. Nucl. Sci. Technol., 48, 1–30, 2011.

Shuttleworth, J., Rosolem, R., Zreda, M., and Franz, T.: The COsmic-ray Soil Moisture Interaction Code (COSMIC) for use in data assimilation, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 17, 3205–3217, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-3205-2013, 2013.

Siebert, S., Webber, H., Zhao, G., and Ewert, F.: Heat stress is overestimated in climate impact studies for irrigated agriculture, Environ. Res. Lett., 12, 054023, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa702f, 2017.

Tack, J., Barkley, A., and Hendricks, N.: Irrigation offsets wheat yield reductions from warming temperatures, Environ. Res. Lett., 12, 114027, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8d27, 2017.

Troy, T. J., Kipgen, C., and Pal, I.: The impact of climate extremes and irrigation on US crop yields, Environ. Res. Lett., 10, 054013, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/5/054013, 2015.

Vereecken, H., Huisman, J., Bogena, H., Vanderborght, J., Vrugt, J., and Hopmans, J.: On the value of soil moisture measurements in vadose zone hydrology: A review, Water Resour. Res., 44, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR006829, 2008.

Wagner, W., Blöschl, G., Pampaloni, P., Calvet, J.-C., Bizzarri, B., Wigneron, J.-P., and Kerr, Y.: Operational readiness of microwave remote sensing of soil moisture for hydrologic applications, Hydrol. Res., 38, 1–20, 2007.

Walker, J. P., Houser, P. R., and Willgoose, G. R.: Active microwave remote sensing for soil moisture measurement: a field evaluation using ERS-2, Hydrol. Process., 18, 1975–1997, 2004.

Webber, H., Ewert, F., Kimball, B., Siebert, S., White, J. W., Wall, G., Ottman, M. J., Trawally, D., and Gaiser, T.: Simulating canopy temperature for modelling heat stress in cereals, Environ. Model. Softw., 77, 143–155, 2016.

Weimar, J., Köhli, M., Budach, C., and Schmidt, U.: Large-Scale Boron-Lined Neutron Detection Systems as a 3He Alternative for Cosmic Ray Neutron Sensing, Front. Water, 2, https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2020.00016, 2020.

Zaveri, E. and Lobell, D. B.: The role of irrigation in changing wheat yields and heat sensitivity in India, Nat. Commun., 10, 4144, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12183-9, 2019.

Zreda, M., Desilets, D., Ferré, T., and Scott, R. L.: Measuring soil moisture content non-invasively at intermediate spatial scale using cosmic-ray neutrons, Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, 21, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL035655, 2008.

Zreda, M., Shuttleworth, W. J., Zeng, X., Zweck, C., Desilets, D., Franz, T., and Rosolem, R.: COSMOS: the COsmic-ray Soil Moisture Observing System, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 16, 4079–4099, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-16-4079-2012, 2012.